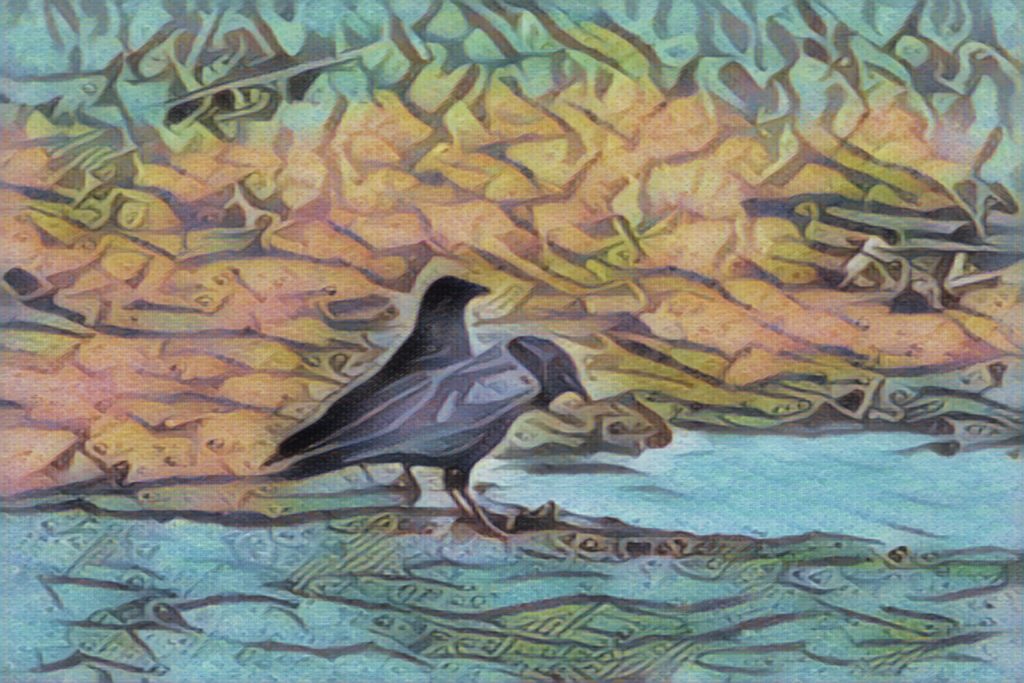

THE LIVES OF TWO CROW SPECIES

link —>Evolutionary genomics in Corvids

Carrion crows and hooded crows are almost indistinguishable genetically, and hybrid offspring are fertile. Two forms remain distinct mostly due Evolutionary genomics in Corvids to the dominant role of plumage color in mate choice. When the planet warmed and the glaciers retreated, the crows re-colonized their original range throughout Europe. But by this time, the two populations of crows looked so different that they rarely viewed members of the other group as being the same species. After living apart for millennia, they had become almost completely reproductively isolated from each other.

They had become in the process of speciation, and were in a process of defining their own species. The southwestern crows gave rise to the carrion crow, which are entirely black, and the eastern crows to the grey-bodied hooded crow. The area where the two forms come into contact and where they occasionally mate is known as the ‘hybrid zone’ Despite their dramatic differences in plumage color, these crows still have similar habits and morphologies, so ornithologists long considered them to be geographic races of just one species. But after careful observations, experts concluded in 2002 these two crows really are different species because they very rarely hybridized. Scientists have been trying to understand the genetic basis for reproductive isolation in the two species of crows.

New sequencing techniques allowed them to find differences in stretches of DNA up to 150,000 base pairs. The only structural variations that they uncovered were involved in plumage color. They found a 2.25-kb insertion mutation in a gene in the hooded crow genome that affects color by interacting with another, distant, gene, and changing its expression pattern. Basically, a difference in just 2,250 DNA letters, out of a total of about 1.2 billion or so may be all that separates these two species. The hooded crow plumage color variant popped up approximately 530,000 years ago.

behavioral data show clear evidence for assortative mating in the hybrid zone. The grey-bodied mutation may have been adaptive for hot regions because the color reduces water loss by reflecting sunlight. Are hooded crows’ dramatic colors created by selfish “jumping genes”? It remains a question for future investigations, no doubt. selfish genes are so successful at inserting copies of themselves throughout a genome that half of the human genome is composed of a variety of them.

Mutations caused by selfish “jumping genes” are common, but they remain undiscovered in most organisms. This study into the lives of two crow species neatly exemplifies the old proverb that ‘birds of a feather flock together’ by describing the genetics underlying what these crows do naturally. The only genes that differ significantly between the two species are those involved in determining the color of their plumage.